“As free mixing was not allowed, the male teacher sat in an adjacent room to the students and used a mic to teach us.”

I went to a part time (3 hours a day, 6 days a week) madrasa that taught a seven year alimah course for girls ages 11+. We were taught Arabic, Urdu, Fiqh, Hadith, and Tafsir. The first five years were taught by female alimahs, and the final years, where we were taught the six authentic hadith collections, were taught by male alims.

This was usually said to be because female scholars were not as qualified to teach the important books. Also, as free mixing was not allowed, the male teacher sat in an adjacent room to the students and used a mic to teach us. There was a hole in the wall that separated our two rooms, which was covered by a curtain, and it would be used to pass books and things to each other, but we never saw each other.

The madrasa followed the Hanafi Deobandi school of thought, and as such its rules were usually quite strict and restricting. The dress code for all pupils was a black scarf and abaya, and a niqab which had to be worn when travelling to and from home. We were taught that the niqab was fardh (compulsory), and often girls who came in without a niqab would be sent home. Music was also prohibited, and we were told that those who listen to music would get molten lead poured into their ears in the hereafter. Talking about such punishments and the afterlife was very common, and we even had a lecture where the speaker turned the lights off and made us lie down and pretend we were in the grave, in order to scare us into being more religious.

Although the website for the madrasa states that it is dedicated to ‘empowering women through education,’ their actual teachings were very different. We were taught that as women, we were to obey our husbands, to the extent that we could not even leave the house without his permission. A woman’s position was said to be in the house, and any contact with non-mahram men was strictly prohibited. We were even told to put on deeper voices if we had to talk to a guy, so he would not be attracted to our soft feminine voices. We were also discouraged from getting jobs that were not in an Islamic setting, and the only job that was encouraged was being an Islamic teacher, which is what almost all of my former classmates have gone on to become.

There was also a lot of homophobia, and homosexuality was seen as a strange and unnatural thing. This issue was actually one of the things I first argued with my teacher about when I started doubting Islam and realised I no longer thought that it was a sin. To his credit though, he was willing to engage and listen, and admitted that if his child was not straight, he would still love them but due to Islam’s rulings, he would be forced to disown them. This teacher was in fact one of the more liberal ones, and was later fired because he was friendly with us and would sometimes bring us food if we were going to have a particularly long lesson, and other staff members thought it was inappropriate for a male to be interacting with female students in this manner.

However, although a lot of the teachers were very strict, some were more open minded. When I first began having doubts about Islam, I confided in one of my classmates and a teacher, and they were both very understanding and we are still friends – even after I eventually told them about my apostasy. Due to this, I actually loved being a student at the madrasa. I highly value the friendships I made with the other students and even some teachers, and the actual learning was both interesting and stimulating. Overall, despite the negatives, I still view my madrasa experience as a highly positive one.

Anonymous

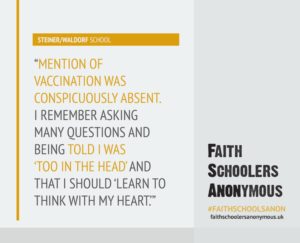

The intoxicating fragrance of beeswax and homemade bread. Small wicker baskets full of pebbles and shells. A biodynamic vegetable garden. Wooden blocks, silk play cloths, felt slippers, sheepskins, a fireplace, faceless dolls, wordless books, formless paintings…

The intoxicating fragrance of beeswax and homemade bread. Small wicker baskets full of pebbles and shells. A biodynamic vegetable garden. Wooden blocks, silk play cloths, felt slippers, sheepskins, a fireplace, faceless dolls, wordless books, formless paintings…